About

The topic of why Godot does not utilize ECS comes up often, so this article will explain the design decisions behind that, as well as shed some light on how Godot works.

Note: In hopes to avoid misunderstandings, I did changes to the article to better stress that this is not an inheritance vs composition or anti-ECS article to spark a flame-war. It only explains the reasoning for which Godot went with its current architecture. I don’t believe there is an universally better way to do things, so if you prefer to use other approaches or architectures that work better for you, then that’s great. Read this if you are interested to understand the reasoning behind Godot’s architecture, not to understand if one approach is better over the other.

What is ECS?

ECS is a design pattern commonly used in video games (although not very often used in the rest of the software industry) which consists of having a base Entity (a container object) and Components that can be added upon it. Components provide data and the means to interact with the whole world. Finally, Systems work independently and do actions on every similar component.

This design became common in game engines and libraries in the early 2010s. The main appeal (besides architecture) is the fact that component data can be placed in contiguous memory, improving cache access. This is a common form of data-oriented optimization.

Architecturally wise, ECS aims to replace inheritance, by favouring composition, similar to how interfaces or multiple inheritance works in OOP. The key advantage in ECS is that components are dynamic (can be added or removed in run-time).

Why does Godot not use ECS?

Godot uses more traditional OOP by providing Nodes, that contain both data and logic. It also makes heavy use of inheritance. It still does composition, but at a higher level (the nodes you compose are generally higher level than components in traditional ECS).

As an example of the difference, in typical ECS, a Button entity can have components like:

- Transform

- Renderer

- EventHandler

- Button

- Behavior

To make it simpler and avoid problems, some implementations force some components to exist when others are added.

In Godot, a Button has the full inheritance chain implicit:

Node -> CanvasItem -> Control -> Button -> Behavior Script

A more complex example can be a rigid body with a sprite attached, in typical ECS, this is found as an entity containing:

- Transform

- RigidBody

- Collider

- Sprite

In Godot, however, this is more complex. You need 3 nodes and hierarchy:

RigidBody (Node -> Node2D -> PhysicsBody2D -> RigidBody2D)Sprite (Node -> Node2D -> Sprite)CollisionShape (Node -> Node2D -> CollisionShape)

So, at first it seems that the approach in Godot is more wasteful, but is it really?

- Node is lightweight, similar to a component.

- Node2D contains the 2D transform, similar to Transform component in ECS. Three nodes are required whereas one component suffices in ECS. This seems wasteful, but is it really? In the entity, the collider and the sprite will most likely not be used centred and will still require offset and rotation properties, so in the end not much changes.

- In Godot adding more of these (multiple sprites and colliders) is kind of free, the transform offset happens automatically. In ECS, special logic needs to exist to take care of this.

As can be seen, inheritance and composition can live together and make sense in the context of Godot.

The main difference can be summed up as:

Godot does composition at a higher level than in a traditional ECS.

This has two fundamental differences in both architecture and performance.

Architecture

Architecture wise, this leads to significant changes over how ECS works:

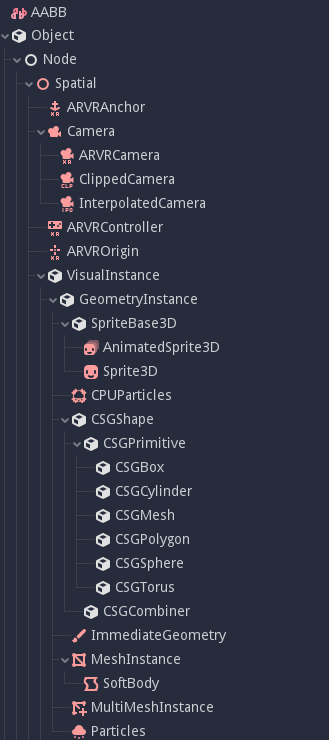

Inheritance is more explicit

As inheritance is preferred (for what would be implicit relationships between components in ECS), these relationships are now explicit in the inheritance chain.

This makes it very easy to understand (to Godot users) how the scene nodes are organized and what they can do, by just looking at the inheritance tree.

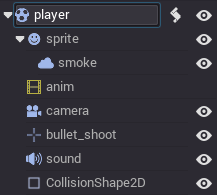

Scenes are more explicit

As composition happens at a higher level (nodes), it’s also very easy for Godot users to understand what a scene actually does by just looking at the scene tree:

Re-usability improves

Thanks to everything being nodes (and not entities with components) it becomes easier to reuse and combine everything as much as possible. This is why Godot does not have the concept or distinction between prefabs and scenes.

Additionally, by having higher level nodes, Godot does not have the concept of “scene settings”, as these is done with nodes too.

The result is a much greater ability to do composition than in a traditional ECS approach. What typically is:

Components -> Entity -> Prefab -> Scene -> World

Godot just has nodes, and a scene is simply a bunch of nodes forming a tree, which are saved in a file. Scenes can be instantiated and inherited with a higher flexibility than in most other tools.

Optimization

Leaving components aside, Godot has no differentiation between Data and System, choosing to bundle everything together in a more traditional OOP fashion. Nodes contain their own logic.

Architectural preference aside, this may seem like a problem on the optimization side. One of the biggest advantages of ECS is the Systems (data-oriented) part, which allows running through a lot of similar component’s data organized in linear memory. This brings huge performance improvements over the way Godot works with nodes.

The key point here is, again, to understand that scenes and nodes in Godot operate at a higher level than in a traditional ECS implementation.

This can be understood by examining the Engine and Game Logic parts separately:

Engine

Godot uses plenty of data-oriented optimizations for physics, rendering, audio, etc. They are, however, separate systems and completely isolated.

Most (if not all) technologies that utilize ECS do it at the core engine level, by serving as the base architecture and building everything else (physics, rendering, audio, etc.) over it.

Godot instead, those subsystems are all separate and isolated (and fit inside of Servers). I find this makes code simpler and easier to maintain and optimize (a testament to this is how tiny Godot’s codebase is compared to other game engines, while providing similar levels of functionality).

The scene system in Godot (nodes) is generally very high level when compared to a traditional ECS system. Most of what goes on happens via signal callbacks (as in, objects collided, something needs to be repainted, button was pressed, etc.). The situations where something needs to be processed every frame in Godot from the user side are very rare, as the engine will manage this internally, taking the complexity away from the user.

To put it simply, nodes are just interfaces to the actual data being processed inside servers, while in ECS the actual entities are what gets processed by the systems.

In other words, Godot as an engine tries to take the burden of processing away from the user, and instead places the focus on deciding what to do in case of an event. This ensures users have to optimize less in order to write a lot of the game code, and is part of the vision that Godot tries to convey on what should constitute an easy to use game engine.

Game logic

Still (while, by far, not the majority) some types of games will see a performance benefit when using ECS in the game logic side.

These are generally games that need to process game logic on dozens of thousands of objects, where data-oriented optimizations become a must, as the amount of pages moved into CPU cache increases by several orders of magnitude, severely affecting performance (and battery usage on mobile devices).

Again, I will stress the point that, while this use case is rare (in contrast, most games are generally just in the hundreds of objects at most, for which the memory access frequency is far more than good enough without cache optimizations), games that require cache optimizations are real and do exist.

Examples of these types of games are:

- City builders (lots of things going on).

- Sandboxes (lots of tiny things need processing every frame).

- Some strategy games (while not the majority, some can use thousands or dozen of thousands of game units at the same time).

- Other AAA games with lots of content going on.

So, does this mean these types of games can’t be made with Godot?

The answer is that, you can still do anything you want, but you need to do it in a different way.

Do clever optimizations

Before going head-on into brute performance, many times you can still rely on clever optimizations. Ever wondered how SimCity could run on a Commodore 64? It did so by alternating which tiles were processed every frame, so it never needed to process thousands of them at the same time (which would be impossible on a 6502 CPU).

Optimizations can vary from not processing everything in all frames, to giving more priority to processing whatever is visible (or close to the camera). Often, these optimizations will reduce the amount of objects that need to be processed by orders of magnitude, and still perform better than going full data-oriented.

Godot provides nodes such as VisibilityEnabler to aid you on this, and upcoming Godot 4.0 has more fine grained control on disabling sections of a scene tree.

Still, this may not be enough for your game, or too much of a hassle. In this case, you may need to simply skip the scene:

Using Servers directly

As mentioned before, Godot puts most of the high performance/low level parts of the engine in Servers. The APIs to servers are fully exposed in and allow you to control the whole engine at the very low level.

Most of the time, even using the servers from GDScript, C# or C++ via GDNative (or modules) is more than enough for the type of games mentioned above. While they might require high performance code for the core game loop, the logic is rarely so complex that a full-blown framework is required for it.

This is similar to just writing the game yourself in SDL/OpenGL, except the rest of the engine is still available for everything else that is not specialized game code (like UI, IO, saving, networking, etc. In other words, the remaining 90% of the game).

Using Compute

Compute (GPGPU) is nearly universal nowadays (supported on desktop and mobile) and allows for huge flexibility and performance optimizations. Godot 4.0 will include easy to use Compute support for highly parallel tasks.

Using ECS

Nothing prevents you to use an ECS solution in Godot. In fact, I strongly suggest to check Andrea Catania’s fantastic work on Godex, which aims to bring a high performance ECS pluggable implementation.

Future

For future versions of Godot we are evaluating (optionally for when you actually need it) cache friendly ways to process similar nodes, separating data and logic in a way similar to how ECS does Systems, but adapted to how Godot works. After all, these type of optimizations are not exclusive to ECS.

Summing up

While architectures and design patterns that aim to solve several problems at once are very tempting to programmers, Godot is developed with a very pragmatic approach.

While it is true that ECS brings advantages to the table, the cases where it can objectively prove to be a benefit towards Godot’s goals are very limited, so it is very hard (for us at least) to justify an architecture change, given they are the exception and not the common rule (and often optimization can be achieved by other, simpler means).

Godot has chosen the path of being user friendly and scalable above all, and we understand that for most cases, due to how the engine is designed, the cases where extreme game logic performance is needed are much lower (as the engine takes takes care of most of the heavy lifting). Still if this need arises, Godot is designed to give you answers on that front, and more options will keep coming over time.