High level please!

Up to now, Godot networking was only limited to UDP, TCP and some high level protocols such as SSL and HTTP. However, for games themselves, the key is how to synchronize state between games. Having to do this manually with low level APIs can be an enormous pain, due to the inherent limitations of the protocols:

- TCP ensures packets will always arrive, but latency is generally high due to error correction. It’s also quite a complex protocol because it understands what a “connection” is.

- UDP is a simpler protocol which only sends packets (no connection required). The fact it does no error correction makes it pretty quick (low latency), but it has the disadvantage that packets may be lost along the way. Added to that, the MTU (maximum packet size) for UDP is generally low (only a few hundred bytes), so transmitting larger packets means splitting them, reorganizing them, retrying if a part fails, etc.

These protocols are also too low level, so using them for creating peers, reliable channels, and network topologies can be a lot of work.

Mid level abstraction

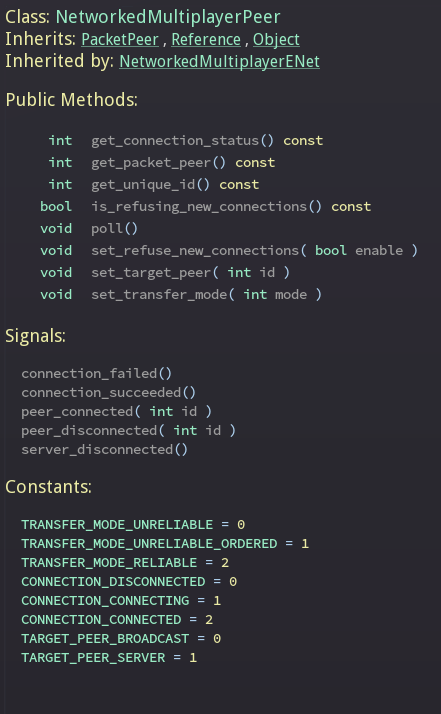

Before going into how we would like to synchronize a game across the network, we need to define how our base network API should be. For this, I created the following interface that would abstract all the low level work mentioned in the previous point:

The new object extends from PacketPeer, so it has all the useful methods for serializing data you are used to, thanks to Godot’s beautiful object-oriented design. It adds methods to set a peer, transfer mode, etc. It also includes signals that will let you know when peers connect or disconnect.

The idea is that this class interface can abstract most types of network layers, topologies and libraries. By default Godot will provide an implementation based on ENet, but the plan is that this could support AdHoc WiFi, Bluetooth, custom device/console networking APIs, etc.

For most common cases, using this object directly is discouraged, as Godot provides even higher level networking facilities. Yet it is made available to scripting in case a game has specific needs for a lower level API.

Ways to synchronize over the network

Early days

The first networked multiplayer games used the modem and LAN. Both provided really low latency and very limited bandwidth. I remember playing Doom 2 and Warcraft a lot in my teenager days, and it worked fantastically over the telephone line. Same thing with the LAN.

As even early games had a lot of things going on, and synchronizing them every frame would mean sending more information than the connection could take, the most common approach was to take advantage of the low latency and simply send the players’ input to each other.

Games were programmed in deterministic ways, so the same input on the same frame would be enough to replicate the state.

Enter Internet

With Internet, connections became more complex, with more routing steps in the middle and longer distances. The bandwidth allowed to send information grew many orders of magnitude, but the latency was also considerably increased too.

Even if a network was infinitely efficient and multiplayer was done with an optical fiber from home to home, you still can’t beat the speed of light. I know it seems odd, but have you ever thought about this?

- The speed of light is 299,792,458 m/s

- The distance between West and East coast of the US is 5,200,000 meters.

This means that the minimum time information takes to reach from one end to the other in the US is 0.0173 seconds. At 60 fps, a computer renders a frame in 0.016 seconds. Whoa, light can be pretty slow if you look at it this way…

Distributed simulation

To compensate for this problem, the most common approach nowadays is to “distribute” the simulation between peers. Generally, each peer will simulate the part of the game “closer” to it.

As such, and given the complexity of this problem, magical solutions where networking “auto synchronizes” don’t really exist, or fail to apply to anything but a simple surface of games.

High level networking in Godot

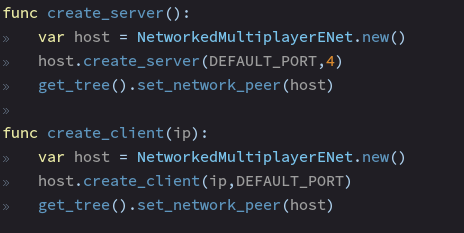

Godot has a new simple but very powerful high level networking API. To get it to work, you must supply a multiplayer peer object to the SceneTree, like this:

Once this is done, networking layer magically functions.

Godot’s high level networking works on the premise that all peers will have a similar scene layout, so the most important priority is being able to synchronize them efficiently.

Synchronizing scenes

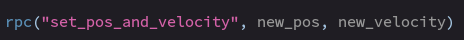

The easiest way to synchronize information between different peers is by using the new rpc() function (RPC means “Remote Procedure Call” – ‘procedure’ is how functions that do not return a value were commonly called in older programming languages).

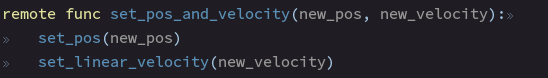

Simply call Node.rpc(<method>, <arguments>), and the function will magically be called in all the other peers. An example, for synchronizing position and velocity across nodes:

This will call a set_pos_and_velocity function in all the other connected peers, thus making synchronization easier. The function would look e.g. like this:

I’m sure that you have noticed this new keyword remote. It means that the function can be called from RPC.

Marking this function for RPC has many uses, but the main one is to simply let you know that it can be called.

Giving peers the ability to call functions in other peers can be really dangerous from a security standpoint. Imagine, what if one peer would open a file in another peer to overwrite system files? This should never happen so, to avoid this, functions must be whitelisted for RPC.

With this scheme, security is just reduced to the few arguments received, making validation easier and lot more difficult for an attacker to cause an unwanted behavior.

Master/Slave model

Synchronizing is fine but, as mentioned before, we mostly care about which peer controls each part of the game. In this new high level networking API, any node can have one of three network modes:

- Master

- Slave

- Inherit

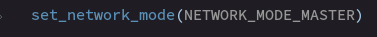

The default one is Inherit, meaning the same as the parent node until a node with something else is found in the parenthood chain. If nothing is set, the server is the master by default (all nodes master), while clients are slave by default (all nodes slave). To change this in a node (and in consequence all its children using the Inherit mode), simply use the Node.set_network_mode() function:

Of course, make sure that there is always one master and that all other same nodes in different peers are slaves.

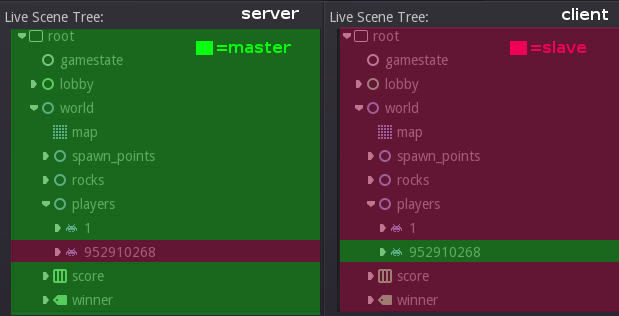

In the example below, you can see the same scene tree in both client and server. Nodes in red are set to slave, while nodes in green are set to master:

For each player we assigned, as their scene names, their unique network ID. This makes it easy to find them (By default, server always has ID=1, while peers have a unique randomly generated ID upon connection). If your game is more advanced, you could use something different such as usernames or something else.

Using the Master/Slave model efficiently

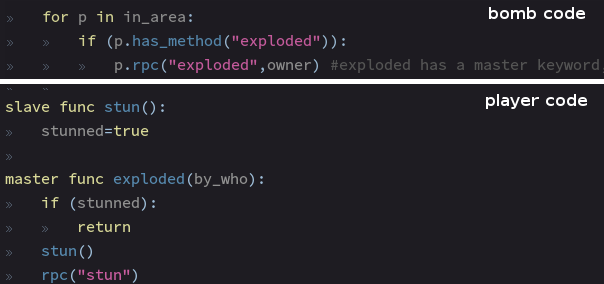

The real advantage of this model is when used with the master/slave keywords in GDScript (Don’t worry we’ll have something similar in C# and Visual Script). Similar to remote, functions can also be tagged with them:

In the above example, a bomb explodes somewhere (likely managed by whoever is master). The bomb knows the bodies in the area, so it checks them and checks that they contain an exploded function.

If they do, the bomb calls exploded on it. However, the exploded method in the player has a master keyword.

This means that only the player who is master for that instance will actually get the function.

This function, then, calls the stun function in the same instances of that same player (but in different peers), and only those which are set as slave, making the player look stunned in all the peers (as well as the current, master one).

Trying it out

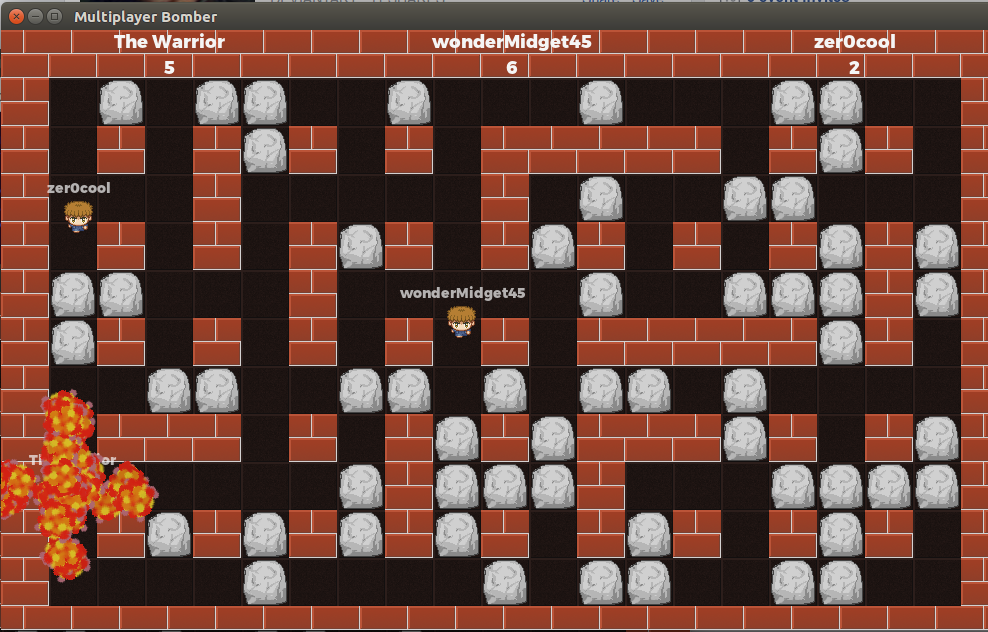

As of today, all these new APIs are available on the GitHub master branch. An example game can be found in the godot-demo-projects repository under networking/simple_multiplayer. No binary builds exist yet, so you will have to compile yourself.

Conclusion

From this first insight, it may not seem very obvious how the high level networking works in Godot. You’ll most likely have to try it yourself to completely “get it”.

The huge advantage of this approach is that, once you are used to it, you can make a multiplayer game with almost the same amount of code as a single player game (save for placing master/slave keywords and calling some functions as RPC instead of regular call). As a plus, your multiplayer game will run single-player just fine without any changes (all nodes will be master, calls to slaves will be ignored).

Please remember that this is a first implementation of high level networking, and we would love to hear your feedback on how we can improve it! Thanks for reading!