Introduction

This project report falls a little bit shorter, as much of the work was less “fruitful” but nonetheless important and a good learning experience. In this case I’m talking about a rather big refactoring of how materials are handled in the GLES2 renderer. Still there were some improvements on the GDNative side of things!

Roadmap

Done March 2018

- C++ bindings for NativeScript 1.1

- WIP godot-rust low level improvements

- perspective rendering

- material API refactor

- material passes and renderlist

- basics for skeletal animations

Planned April 2018

- finish up skeletal animations (- blend shapes)

- stabilize 3D rendering (unshaded workflow)

- implement backbuffer copy

- learning about PBR

- cubemap filter

Details about work in March 2018

C++ bindings for NativeScript 1.1

As talked about in the last progress report, a new extension to the NativeScript API has been added. Now it was time to make use of those new functions in the C++ bindings.

The biggest user-facing change in the bindings is, that user-created classes can now directly inherit from engine types. This is being implemented by facilitating object instance binding data.

Until the new NativeScript 1.1 extension will be more widely used, a system of delegation is used in the bindings to access “parent class” functionality. The GodotScript template class includes a field owner, which refers to the Object that the current script is attached to.

Even though Godot’s scripting languages try to make you believe that you can “extend” or “inherit” engine types, all that is done is actually delegation. Most GDNative language bindings make that explicit, but after receiving some user feedback it was time to fake inheritance in the C++ bindings as well.

Before, every C++ bindings wrapper class was actually more like a wrapper interface with nice syntactic sugar. (I don’t want to say how it is done, I want to keep the little reputation that I have. If you really want to know, all I’m saying is: you can re-use the this pointer “safely” (putting more quotes looks dumb) as long as you don’t have any virtual methods to call…)

That meant, that you couldn’t inherit directely, but now that it’s possible to create per-object binding data, it is possible to create wrapper classes that are proper classes, which can be inherited!

A lot of text and no code so far, so here you go!

Old way:

class MovingSprite : public GodotScript<Sprite> {

GODOT_CLASS(MovingSprite)

Vector2 direction = Vector2(1.0, 0.0);

float speed = 50.0; // pixels per second

public:

void _init() {}

void _process(float delta) {

Vector2 motion = direction * speed * delta;

owner->set_position(owner->get_position() + motion);

}

static void _register_methods() {

register_method("_process", &MovingSprite::_process);

}

};

New way:

class MovingSprite : public Sprite {

GODOT_CLASS(MovingSprite, Sprite)

Vector2 direction = Vector2(1.0, 0.0);

float speed = 50.0; // pixels per second

public:

void _init() {}

void _process(float delta) {

Vector2 motion = direction * speed * delta;

set_position(get_position() + motion);

}

static void _register_methods() {

register_method("_process", &MovingSprite::_process);

}

};

To test those things (and some others, work from April is already available), check out the nativescript-1.1 branch of the C++ bindings here, as well as an updated version of the C++ SimpleDemo on the cpp-nativescript-1.1 branch of the GDNative-demos repository here.

WIP godot-rust low level improvements

Steadily gaining more popularity, the godot-rust bindings are getting more attention from new contributors. I tried to check out the new bindings and notices some problems in the workflow for testing the bindings, so I added small complete godot projects to the repository, so things can be reasoned about in context, with all the scenes and environment in place.

Further, the Rust bindings make heavy use of macros for the “script-class” definition, some users said that the heavy use of custom syntax can be distracting and makes things less clear. This is tracked in an issue, but I thought it could be a fun way to get more into the current and new codebase.

Most of my efforts have been focused on being able to define script classes without needing macros, while still offering some useful macros that are completely optional.

Here is a link to a file to show what “low level class registering” might look like in future (this is already working code).

NativeScript classes expose some function pointers with C linkage with a certain signature. To ease the “connecting” of the C-compatible function and the actual Rust function, a macro has been added that generates said C function which will automatically call the Rust code. This is completely optional, the C function can be created manually, but this is generally not a nice thing to spend your dev-time on. The same has been done for constructors and destructors.

The work-in-progress commit can be found here, I plan to open a pull request as soon as I finish up the commits properly.

perspective rendering

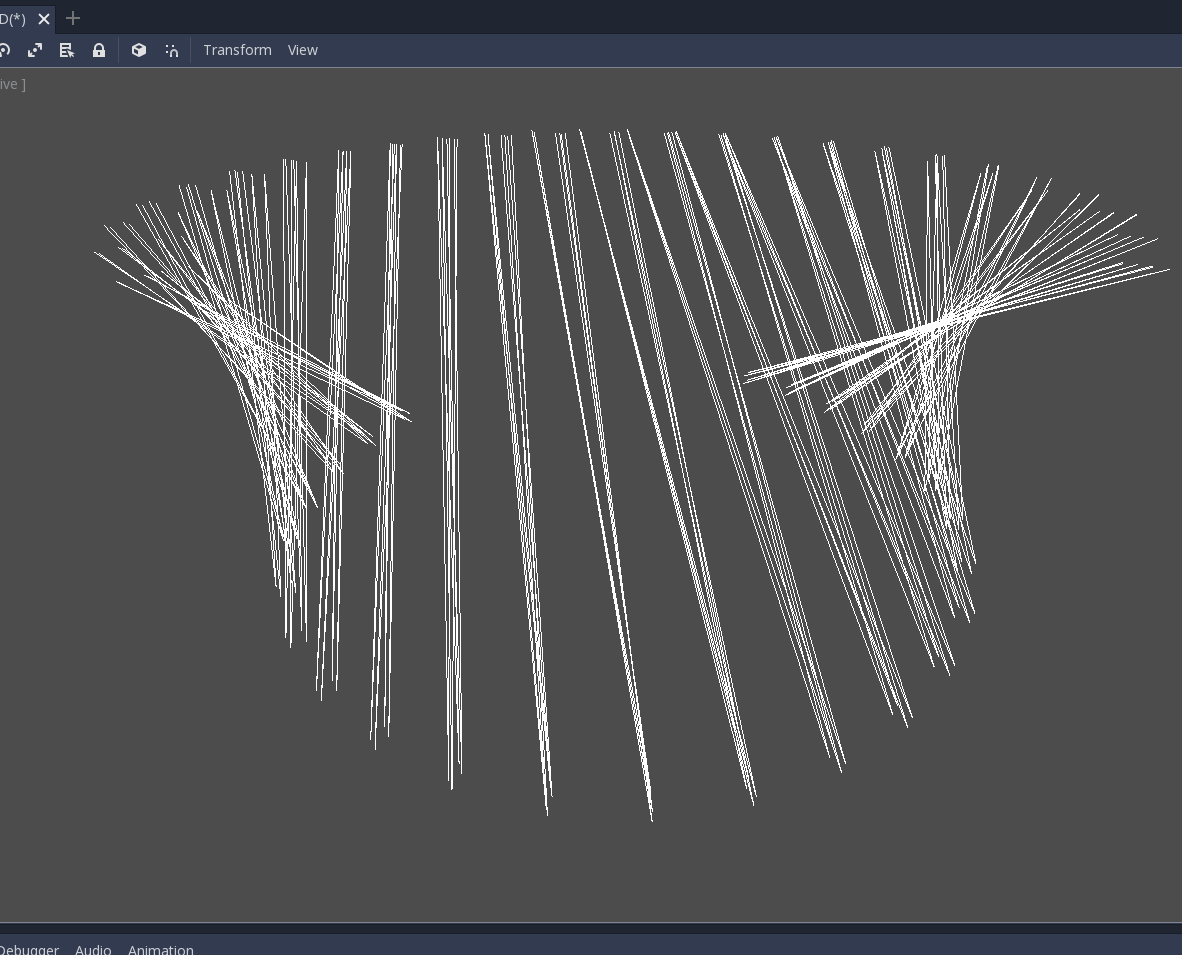

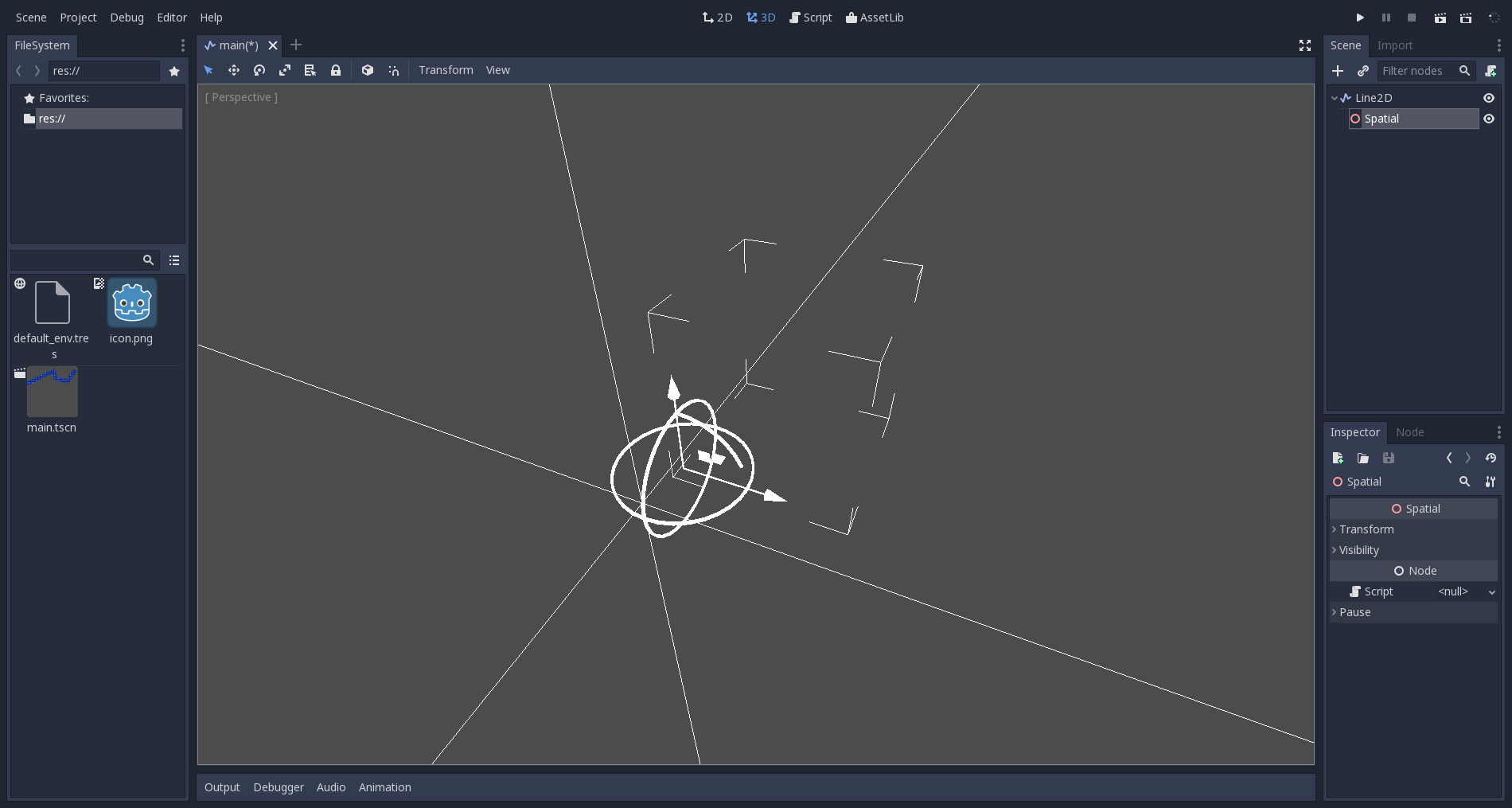

Now finally the more visual part of the progress report! Last time I promised more fancy screenshots, here some perspective-correct renderings of some meshes.

No color, no grid on the ground…? Yes, some more invalid OpenGL state was fixed and a first attempt to get spatial shaders working and then this could be seen.

Getting there, slow but steadily :D

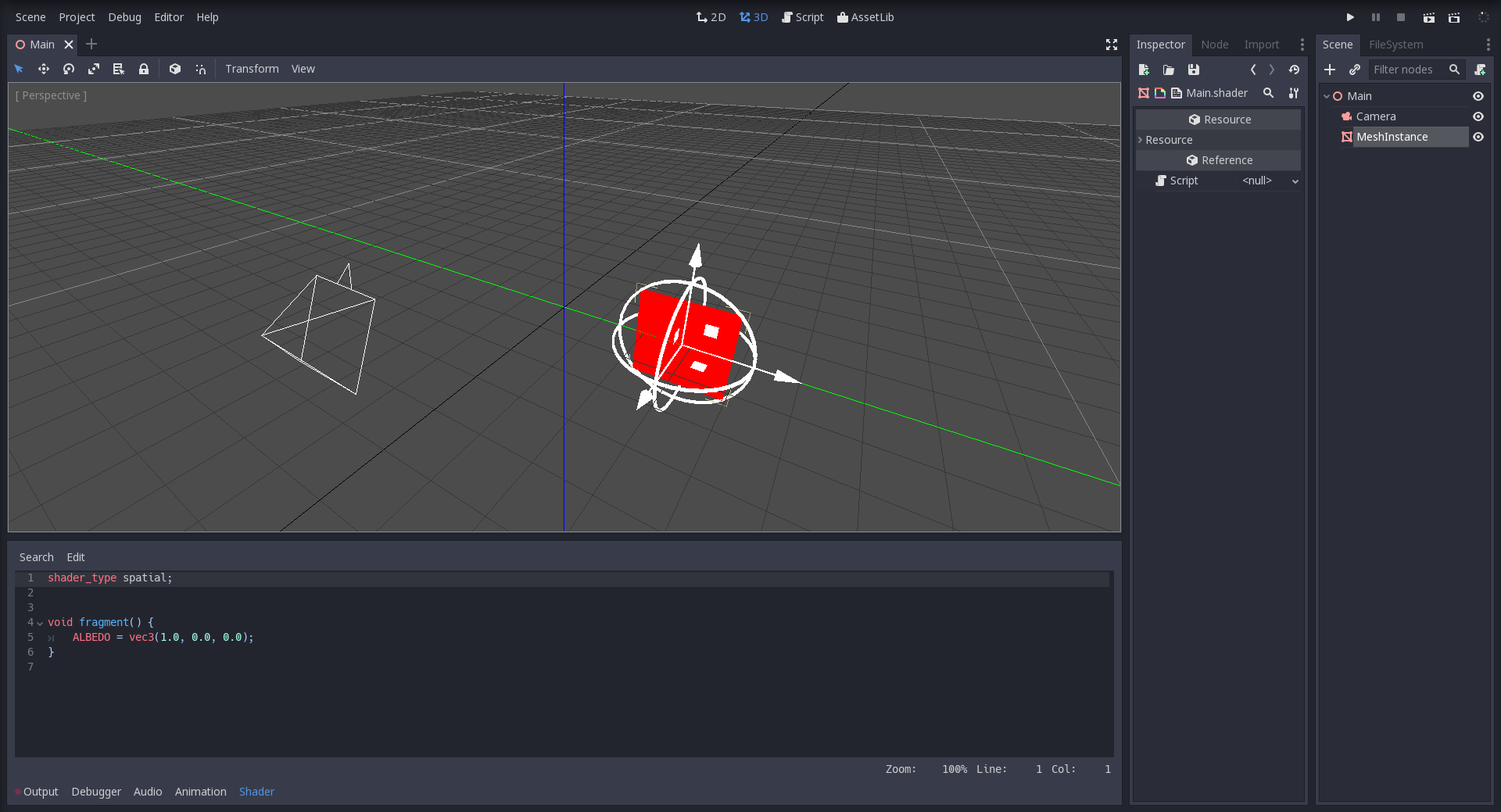

material API refactor

This point actually took most of the development time this month, it was a rather frustrating and iterative process to find out how to best handle materials and shaders.

Some background on materials first!

In Godot, a material basically consists of a shader and a list of parameters (name => value pairs) that get passed into the shader. Materials also include other things, like blend modes but the problematic part were the material parameters.

Since OpenGL 3.1, Uniform Buffer Objects, short UBOs, can be used. UBOs are chunks of memory that contain data that is available “globally” and immutably in every shader stage.

The TIME variable in shaders? Part of a UBO. Texture handles? UBO. Camera projection matrix? Also UBO. Those things don’t change in a single draw pass, so they get grouped into a buffer which can then be updated all at once.

In the GLES3 renderer, material parameters get assigned an offset in a UBO, then that UBO can be filled and used for a draw call.

In GLES2 however, UBOs do not exist. Every uniform (a “global” value accessible in all shaders) has to be set individually for each shader.

This is where many iteration and refactoring have been focussed on. Do those values get set when the material changes? No, drawing might happen later in time and the uniform value lost. Do the values get saved in the shader and the shader sets them up when needed? This is rather complex when user-defined shaders come into play, it’s possible, but it doesn’t feel right and caused many bugs.

After all those iterations, I settled for an approach where the shader gets a reference to the material that will be used, and then, only when the shader will be used for drawing, the shader will set all uniform values accordingly.

Some type-system hacks are needed because C++ doesn’t like forward declared inner classes (if someone knows how to do it, please, tell me :D ), and I came up with this code. There is a lot of code that deals with getting and selecting the right uniform type/call, but this way the information from custom shaders can be used more efficiently. With UBOs, this comes natural, and very similar code exists in the GLES3 renderer.

In the end, this approach works pretty well and seems very clear to me, and after all those refactoring I can safely say: UBOs are missed. :D

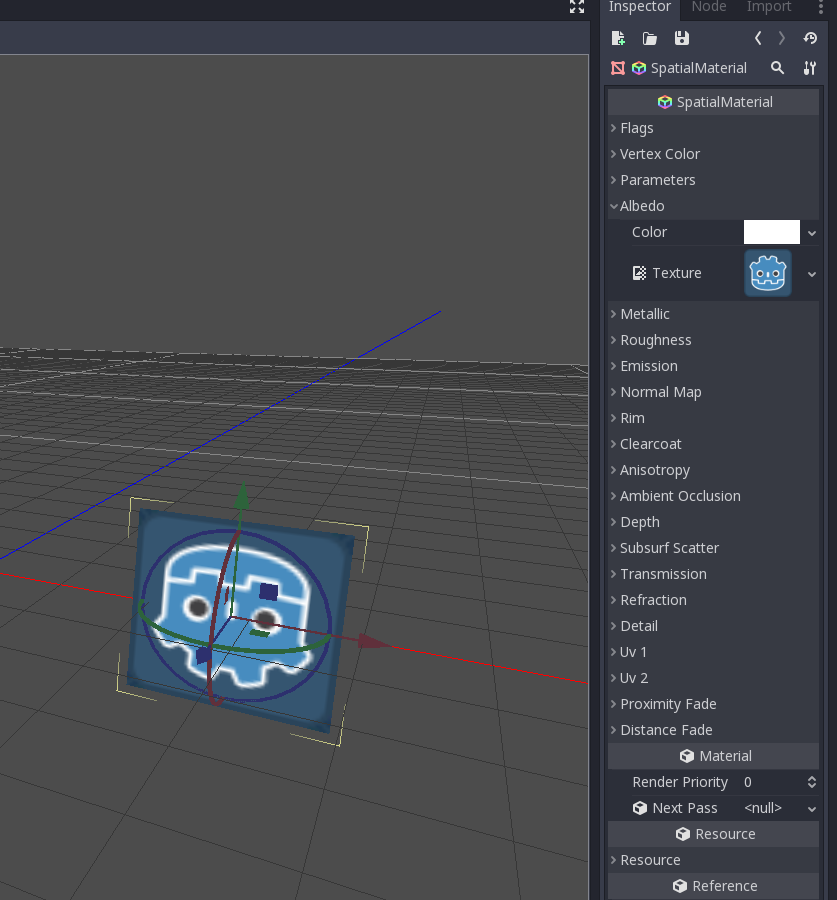

material passes and renderlist

Up until that point (well, the refactorings and this kind of blend together, but I hope it’s clear what I mean) the drawing was very straighforward.

- Get the next available thing to draw

- if you can draw it, set the GL state up properly

- render.

The code was relatively small and rather simple to understand and get an overview over, because it was so straighforward. But as with many things, this simplicity becomes problematic at some point. In this case no optimization was done at all. Material passes weren’t possible and dealing with shader state became a pain, so it was time to move to a more flexible implementation: the renderlist!

The RenderList is an array of elements and a list of pointers to those elements which need to be drawn.

The cool thing is, that each element can get an index assigned on which they can be sorted. So things in the front will be drawn before things in the back, that helps to reduce overdraw by making use of the depth-buffer. Meshes with similar shaders can be grouped together so that shaders don’t need to be unloaded and loaded again, and many other cool things.

While filling this list, it is very easy to add in a second draw pass for a surface with a different material. This is how the Next Pass in materials is implemented.

The RenderList gives much flexibility while also making simple optimizations very easy to set up.

basics for skeletal animations

Another under-the-hood development was the initial work on Skeleton resources. At that point, a skeleton could not deform a mesh yet and wasn’t very useful, but the basic storage for bone transforms was already in place. Depending on the hardware that Godot is running on, the bone information might be stored in different ways, so the skeleton resource might be handled in different ways.

Because the GLES2 renderer will run on a lot of low-end hardware, I chose a more software-oriented than hardware/GPU-oriented approach to store the bone transforms, but more on that in the next

Future

In the next progress report I will talk about how the new renderer handles skeletal animations differently than the 2.1 renderer, also I will share my then newly-gained knowledge of physically based rendering! Interesting times ahead!

Seeing the code

If you are interested in the GLES2 related code, you can see all the commits in my fork on GitHub. Other contributions are linked in the sections above.