It’s been a while since my last report because this particular task took me more time than I anticipated. GDScript now got a much needed optimization.

See other articles in this Godot 4.0 GDScript series:

- GDScript progress report: Writing a tokenizer

- GDScript progress report: Writing a new parser

- GDScript progress report: Type checking is back

- GDScript progress report: New GDScript is now merged

- (you are here) GDScript progress report: Typed instructions

- GDScript progress report: Feature-complete for 4.0

Bug fixes

Between my last report and this one I’ve been fixing many bugs in the new GDScript. While not thorough, it should be stable enough to not crash all the time. I am aware that a lot of bugs remain, but I’ll iron them out when the features are complete.

As I said before, if you found a bug not yet reported make sure to open a new issue so I can be aware of it.

Code generation abstraction

Before I delved into the interpreter, I created another class for abstracting the code generation process in the compiler. This allows new targets to be added without messing with the compiler itself by just adding a new implementation of that abstraction.

That should allow us later on to more easily add new targets like compiling to LLVM or C (note that those ideas are not settled, we still need to investigate the best way to do it). It also might simplify how we apply an optimization phase to GDScript code.

This doesn’t yet have a pluggable interface, so it’s hardcoded for the single target that we have for now (the GDScript interpreter itself) but once we have new targets we can easily adapt to our needs.

Typed instructions

I know many of you have been waiting for this. GDScript has had optional typing for quite a while, but so far it had only been for validation in the compilation phase. Now we’re finally getting some performance boost at runtime.

Note that some optimized instructions are applied with type inference but to enjoy the most benefit you have to use static typing for everything (you also get safer code, so it’s a plus).

So what kinds of instructions do we have? Here’s a short list:

- Operations (such as

+,or,&, etc.), when the type of the operands are known. - Subscript/attribute access (like

a[b]anda.b), when the types of both the base and index are known. - Function calls for built-in and native (C++) types, when the base type is known.

- Those get special cases when argument types are also known.

- Built-in function calls (like

sin(),randi()), when the type of the arguments are known.- Note that arguments that require conversion might not get a faster path.

- Iteration (use of

forloop) when the type of the iterated value is known.

Doesn’t sound like a lot but since those got a lot of variations for the type combinations, the number of instructions got quite a bit larger. Those are the most used and where performance matters more.

Why is this faster?

Having specific instructions for when type is known allows us to take shortcuts in the interpreter. For example, if we know we are adding two integer values, we can take the pointer for the integer values from the Variants and just add them (literally a + in the C++ source code). Before we had to not only look up the types of the operands but also the operation itself at runtime which takes a while.

Function calls for native types are also a very special case since we can take a pointer to the function and call it directly when the arguments are already validated. This is what is used in GDNative and C# for instance, since they have static typing by default.

How faster is it?

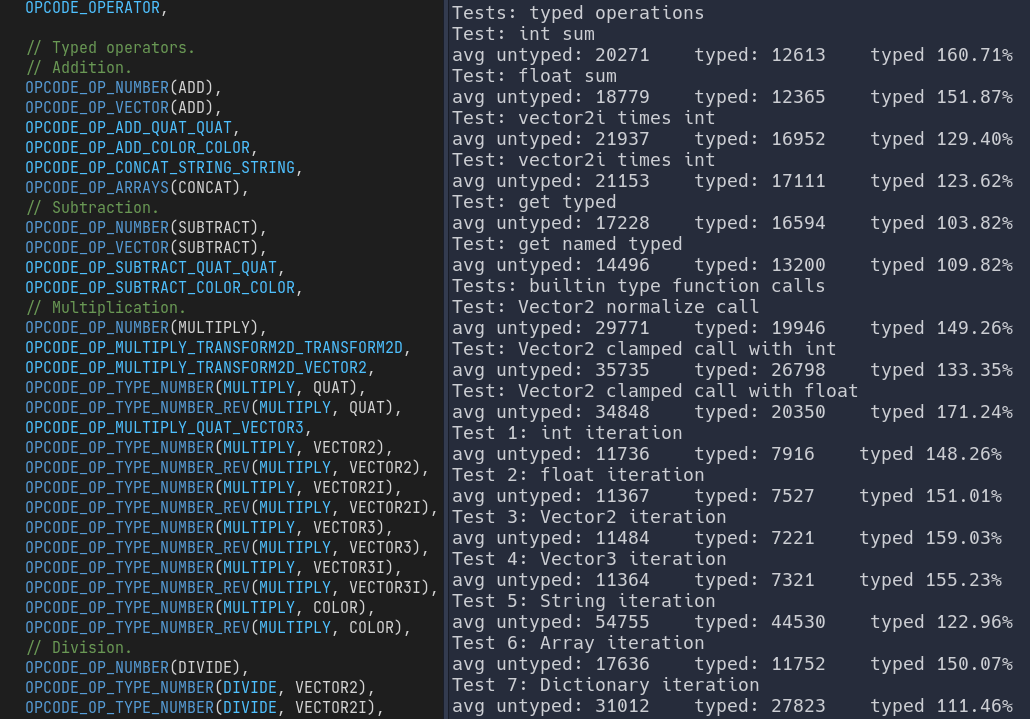

I have made a few synthetic benchmarks to test how faster a typed instruction was than a regular untyped one. This consisted in running all in a loop and measuring the time it took. Assuming the loop takes the same amount of time in both cases, the difference in time should be the instruction itself. Typed instructions are consistently faster in all tests.

- Subscript/attribute: about 5-7% faster

- Operations: about 25-50% faster

- Function calls in built-in types (without pre-validated arguments): about 30% faster

- Function calls in built-in types (with pre-validated arguments): about 70% faster

- Function calls in native classes (without pre-validated arguments): about 70-80% faster

- Function calls in native classes (with pre-validated arguments): about 120-150% faster

- Built-in function calls: about 25-50% faster

- Iteration: about 10-50% faster (dictionaries and strings have a lesser performance gain)

Those were measured with a debug build. It should perform better with release builds.

Can it be more optimized?

Yes, there are still room for further optimization. But since it can get quite complicated we left this for a later review. There are some inner working in the VM that could be better. For instance, we could reduce the type changes in the stack (when they are attributed a new value) which reduce the operations needed to perform the instructions, making them faster. We could also improve type inference to rely less on static typing and allow simpler code to still get a speed boost.

Also, code in GDScript is not yet optimized by the compiler. Once we reach that it’ll certainly improve overall speed of execution of the scripts.

I want to point out GDScript is not as slow as some imagine. Much of what you do is leveraged to the engine internals, which are built in C++ and optimized already. In my tests I had loops of 100,000 iterations and even the function calls (which are generally slower) were hitting about 70ms for running the whole loop (sure I do have a somewhat good CPU, but this is running single-threaded in debug mode). While it might be a bit slower than other languages, it’s definitely up for the task at hand (that is, making game logic).

Future

Now that this first optimization of the VM is complete, I’ll be a bit away from GDScript to focus on GDNative. Since it doesn’t have a dedicated maintainer anymore and it needs many improvements, especially on the usability side. We’ll meet with coredevs familiar with GDNative to decide what needs to be done and start working on it.